The events in the levant since October 7, 2023, are redefining the status quo tension between Israel, Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran. Israel has now shifted from operations in Gaza to the north and a focus on Hezbollah. The death last week of Hassan Nasrallah and other Hezbollah senior leaders on the heels of the preceding dramatic pager and walkie-talkie attacks has left Hezbollah and Tehran off balance as they consider their next steps. IDF Chief of Staff General Herzi Halevi’s warning in the wake of the strike that killed Nasrallah, “This is not the end of our toolbox. The message is simple, anyone who threatens the citizens of Israel - we will know how to reach them”. With the start of the IDF’s limited ground assault into southern Lebanon, the conflict has entered a new and dangerous phase.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced Israel’s goal of returning 60,000 Israeli citizens to their homes in northern Israel who have been displaced for nearly a year as a consequence of Hezbollah rocket attacks. The goal would almost certainly necessitate clearing Hezbollah’s presence from southern Lebanon – an enormous and complex task. This is not a new task. The IDF has tried similar operations before, during Operation Litani I (1978), Operation Peace for Galilee (1982), and most recently, the 2006 Lebanon War, but the challenges today are more than ever before.

In Operation Litani (1978), the IDF sought to push back Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) fighters beyond the Litani River (30 km north of the border) who were using southern Lebanon as a base to launch cross-border attacks. The operation succeeded in temporarily moving the PLO away from Israel’s northern border, but it did not eliminate the threat entirely.

Similarly, Operation Peace for Galilee (1982) was designed to neutralize the PLO and create a security zone in southern Lebanon. The IDF invasion ultimately drove Yasir Arafat and his PLO fighters out of Lebanon under escort by a four-nation Multinational Force. Hezbollah rose to prominence, filling the vacuum left by the PLO, and claimed victory when Israel withdrew from Lebanon in 2000 after 18 years of occupation.

By 2006, Hezbollah was firmly entrenched in Lebanon when the Lebanon War (also known as the Second Lebanon War) broke out.

The 2006 Second Lebanon War revealed critical weaknesses in both Israel’s strategic planning and its execution of a complex military campaign. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s government and IDF leadership initially believed that a robust air campaign would suffice to dismantle Hezbollah’s capabilities. Hundreds of Israeli Air Force (IAF) sorties targeted Hezbollah’s command and control structures, missile launchers, and supply lines. However, it soon became clear that an air campaign alone would not neutralize Hezbollah’s missile threat.

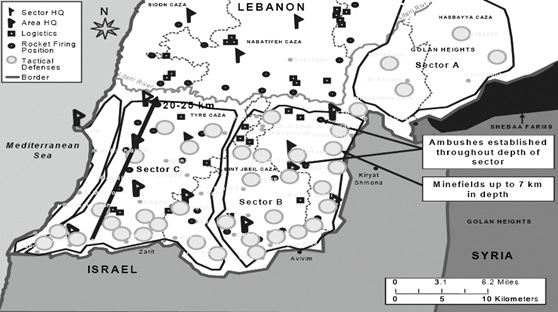

However, they came late to the realization that a supporting ground campaign was necessary. What followed was a hastily planned and quickly executed ground phase where IDF forces crossing into Lebanon discovered a new type of Hezbollah defense that used the dense terrain and vegetation of south Lebanon laced with concealed bunkers equipped with hidden rocket and missile launchers, advanced anti-tank weapon systems, stockpiled logistics and astride population centers designed to present the maximum threat to armor heavy Israeli forces. These defensive compartments were dubbed “nature reserves.” The mobile armor-heavy IDF was unprepared for this type of warfare.

Over the course of the 34-day-long war, 49 civilians and 121 IDF soldiers were killed, and over 2,500 civilians and soldiers were wounded. Most IDF combat casualties occurred in the ground war phase. Throughout, thousands of Lebanese were killed or wounded in the crossfire while Lebanon’s economy and infrastructure, particularly in southern Lebanon, was devastated. Hezbollah survived the onslaught but was badly damaged. Afterward, Nasrallah regretted Hezbollah’s decision to fight the war.

The IAF destroyed nearly all of Hezbollah’s medium and long-range rocket systems, such as the ZELZAL-3, with a 200-250km range and a 900KG warhead, and the FATEH 110 road-mobile ballistic missile with a 500kg warhead, in only a few days at the beginning of the war. Despite these successes, the IDF was not able to adequately address and slow attacks from the harder-to-find, low-signature Katyusha rockets. These old unguided rockets are simple and effective, with a range of up to 45km and a warhead of approximately 5kg of high explosives. Hezbollah gave its leaders a large degree of autonomy in launching rockets and conducting independent sustained fire. Almost a week after the outbreak of the war, it became clear that Hezbollah was launching hundreds of Katyushas a day almost uninterruptedly and that the war could not be decided from the air or via firepower. The threat from Katyusha rockets remains unresolved and will likely remain a significant impediment to ensuring a safe and secure northern Israel.

During the war, Hezbollah fired nearly 4,000 rockets on Israeli population centers of its purported more than 10,000 rocket and missile holdings, with 300 rockets fired in the hours before the UN-sponsored ceasefire as a final signal that they were not defeated.

Aftermath of the Second Lebanon War

The events of the past weeks in Lebanon have similar parallels to previous conflicts. In the nearly two decades since 2006, both sides have made adjustments in their force capabilities. Hezbollah has significantly strengthened its missile and rocket forces which are now estimated between 120,000 – 130,000, and some estimate as many as 150,000 missiles, including long-range missiles capable of reaching the entire State of Israel: sophisticated anti-tank weapons, dozens of unmanned aerial vehicles, advanced anti-ship missiles, advanced anti-aircraft missiles, and aerial defense systems.

Prior to the outbreak of fighting in 2023, Hezbollah had massively expanded and broadened its inventory of short, medium, and long-range rocket and missile systems, enhanced lethality by retrofitting rockets with precision guidance systems, and enhanced rocket and missile survivability by the employment of deception and dummy site techniques.

In addition to its traditional rocket and missile forces, Hezbollah has invested heavily in drone technology. Drones have become a key part of Hezbollah’s military strategy, offering a flexible and relatively inexpensive way to gather intelligence and launch attacks. As of mid-2024, Hezbollah was estimated to possess around 2,500 drones, including both surveillance UAVs and so-called "suicide drones" or loitering munitions designed to strike targets by crashing into them.

Drones offer several advantages over traditional missile systems. They are smaller, harder to detect, and can bypass Israel’s advanced air defense systems like the Iron Dome and David’s Sling. In May 2024, Hezbollah launched one of its deepest drone strikes into Israel, targeting a major Israeli Air Force surveillance system and scoring a direct hit. This marked a significant escalation in Hezbollah’s use of drones and underscored the challenges Israel faces in defending against these new threats.

On June 13, 2024, Hezbollah launched its largest drone assault since the conflict began, with 30 suicide drones and 150 rockets directed at 15 Israeli positions. In a full-scale war, Hezbollah could try to overwhelm Israel’s Iron Dome system using a combination of drones, rockets, and missiles.

Hezbollah relies on Iran as its main supplier of drones, although they have begun to manufacture and assemble their own drones and adopt new technologies, such as investing in racer drones remotely controlled by goggles. Hezbollah is increasingly using low-flying drones to gather intelligence and to attack for which Israel has no comprehensive solution.

Since October 7th, 2023, Hezbollah has continuously fired rockets and missiles into Israel. Despite the decapitation of Hezbollah’s leadership and the hundreds of sorties Israeli Air Force (IAF) has flown against Hezbollah targets in Lebanon, Hezbollah retains the capability and intent to confront Israel.

Today, Israel is conducting a major air campaign in Lebanon, primarily targeting rocket launch sites to degrade Hezbollah's capabilities. For one day, on 28 September, the IDF reported that it struck approximately 800 Hezbollah targets in southern Lebanon. Targeting the relatively mobile and extremely well-hidden Hezbollah rockets, missiles, and drones is a difficult undertaking. The Second Lebanon War lesson is that airstrikes alone were not able to stop Hezbollah rocket barrages, and a ground invasion was necessary.

Any ground campaign would be costly, both in terms of Israeli casualties and the potential for widespread destruction in southern Lebanon. Hezbollah’s fighters are well-prepared to resist an IDF assault, with extensive knowledge of the terrain and a network of fortified positions designed to withstand Israeli air and ground attacks. Late in the 2006 war, the IDF attempted helicopter-borne operations to get behind the nature reserves, but these operations were piecemeal and late to be part of the IDF's overall strategy.

Although Hezbollah’s leadership has been removed, their dramatically expanded post-2006 rocket and missile capability remains intact and a threat. New technologies and drones have added depth and increased options to Hezbollah’s lethality. What remains to be seen is if Hezbollah will fight and how their use of the same terrain and new capabilities may have changed since 2006. How Iran will respond to bolster Hezbollah and protect Tehran’s influence in the region is yet to be seen. The current conflict has a similar parallel, taking a similar path. The lessons of the Second Lebanon War loom large. Time will tell what lessons from the past have been learned and how strategies and operational plans are adjusted to account for new technologies coupled with enduring threats.

Right now, as I prepare this post for release, news platforms are reporting that the Israeli military has announced “a limited ground operation” in southern Lebanon targeting Hezbollah has begun. The next question is, “What does limited mean?”

From the Book Vault

For an in-depth accounting of the 2006 war, Amos Harel and Avi Issacharoff’s 2008 book, 34 Days; Israel, Hezbollah and the War in Lebanon is a first account that provides a day-by-day chronicle of the war from the border abduction of an Israeli soldier on the morning of July 12, 2006, through the hasty decision for an aggressive ground campaign. 34 Days gets into PM Olmert’s cabinet deliberations on strategy and decision-making and dives into how the IDF’s flawed strategic approach, a lack of understanding of the terrain, and Hezbollah’s thorough preparation to combat an IDF invasion, to the lack of timely, imaginative planning led to missed opportunities and ultimately, a failed campaign.

For a deeper analysis of the Second Lebanon War, look at Dr. Anthony Cordesman with George Sullivan and William D. Sullivan's Lessons of the 2006 Israeli-Hezbollah War. In this volume, they assess all aspects of Israel's goals in the war, from stopping Iran’s influence and Hezbollah’s growing grip inside of Lebanon, to securing the return of the two captured Israeli soldiers which triggered the war’s outbreak. Cordesman does a thorough job of examining the tactics used to achieve those goals, outlines the major lessons regarding the conduct of the war and its tactical and technological aspects, and shows that conventional forces can be vulnerable to asymmetric attacks on the battlefield, which precipitates political problems. Cordesman provides a timely assessment of flawed war planning, overreliance on high-technology conventional warfare while not adapting to the adversary’s use of asymmetric warfare, and a strategy that underestimated the strength of the enemy.

From Beirut to Jerusalem by Thomas Friedman (1989). Chronicling his days as a reporter in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War and in Jerusalem through the first year of the Intifada. Friedman offers a keen, even-handed viewpoint revealing the savagery and brutality that characterizes all sides of the conflict.

David Crist’s The Twilight War: The Secret History of America’s Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran (2012) provides an excellent and insightful examination of how the United States and Iran went from close allies to enduring enemies. He traces the intervening years of the multifaceted conflict, illustrating its evolving complexity and its continuing contemporary influence upon the Mideast.

Tags: Future History

"However, it soon became clear that an air campaign alone would not neutralize Hezbollah’s missile threat." This very important observiation and conclusion is one I think many U.S. military leaders are reluctant to accept.